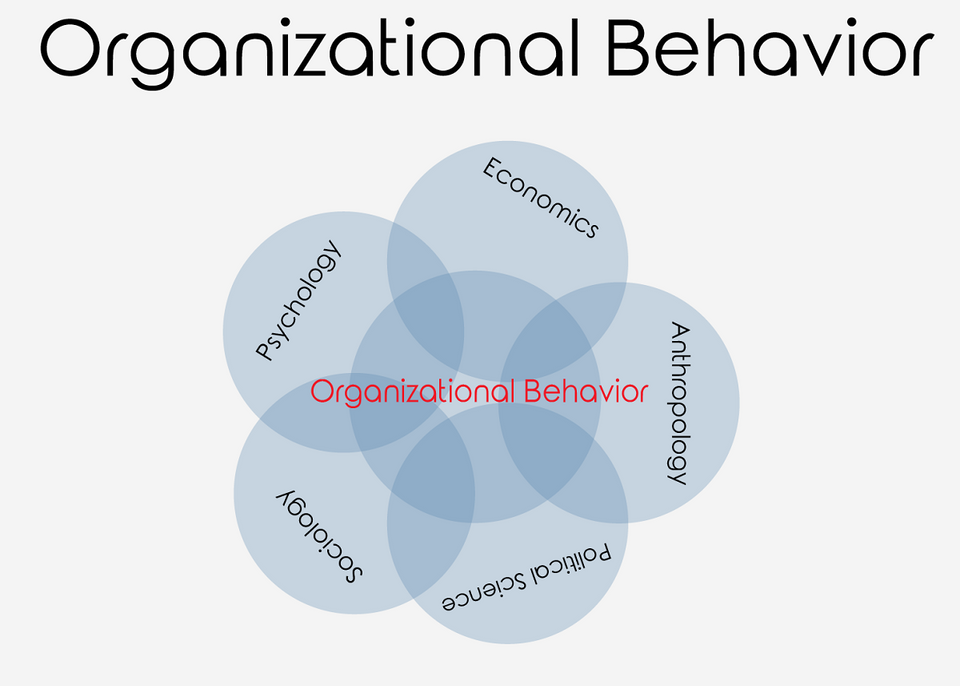

What Is Organizational Behavior and Where Does It Come From?

Organizational Behavior (OB) is "a field of study devoted to understanding, explaining, and improving the attitudes and behaviors of individuals and groups" 1 — with the ultimate goal of explaining and predicting behavior in organizational settings. Understanding the origins and development of OB is crucial to appreciate its practical applications and relevance in today's organizations. OB fits under the social science umbrella as a scientific study and utilizes the scientific method to evaluate and test behavior-related theories and hypotheses. OB studies are typically dedicated to improving job performance, increasing job satisfaction, promoting innovation, and encouraging leadership. At the same time, practitioners use it to bring out the best in employees and improve the overall success of an organization. As a multidisciplinary field, anthropology, psychology, sociology, political science, and economics have all contributed to the research supporting OB. In the following sections, I provide a brief overview of each field and explain how its research has contributed to Organizational Behavior.

Anthropology:

"Anthropology provides a scientific basis for dealing with the crucial dilemma of the world today: how can peoples of different appearance, mutually unintelligible languages, and dissimilar ways of life get along peaceably together?" – Clyde Kluckhohn 2

In its most basic sense, anthropology is the study of humankind. Subfields of anthropology include:

- Archaeology (the study of the past).

- Biological anthropology (the study of human evolution).

- Cultural anthropology (the study of human diversity at the macro level).

As you could imagine, the cultural anthropology subfield holds a lot of insights into how we think as humans, especially within groups and organizations, making it an important anthropology subfield for OB to pull from. There is a significant difference in the way individuals think and act in organizations depending on where they are from. Organizations in western cultures tend to be individualistic, whereas eastern cultures tend to be collectivistic. For example, in collectivistic societies like Japan or China, organizations are much more focused on workgroup goals and hierarchical organizational structures above individual goals and systems that are more lateral. Likewise, individualistic societies like the United States are more focused on individual goals and personal growth; this information originates from research done by cultural anthropologists.

Psychology:

"Understanding human behavior in the context of organizations is the raison d'être for the field of organizational psychology." – Eduardo Salas, Scott Tannenbaum, Kurt Kraiger, and Kimberly Smith-Jentsch 3

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), psychology studies the mind and behavior. This broad definition leaves room for dozens of subfields, one of which Organizational Behavior resides (under Industrial/Organizational Psychology). Even though OB resides within the I/O subfield, it also pulls knowledge from other psychological subfields, including cognitive, educational, health, personality, and social psychology. Because OB pulls so much of its knowledge from psychology, it is possibly the most important of the five subfields. Topics in OB that rely on knowledge from psychology include organizational behavior, change management, career coaching, and more. Goal-setting theory, for example, is the idea that people perform better when given clear and distinct goals; it focuses behavior in the direction of goals by (1) clearly establishing the goals, (2) reinforcing the behaviors that are conducive to achieving those goals, and (3) issuing rewards to the level at which an individual met those goals. The goal-setting theory stems in large part from B.F. Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning is that behaviors that lead to the completion of goals are reinforced with guidance and rewards.

Sociology:

"In the social jungle of human existence, there is no feeling of being alive without a sense of identity." – Erik Erikson 4

Sociology is defined by the American Sociological Association (ASA) as the study of social life, social change, and the social causes and consequences of human behavior. Organizations are complex systems of social rules, norms, and values; OB topics that rely on sociology knowledge include group dynamics, communication, leadership, culture, norms, and more. Group norms, for example, are concerned with the unwritten rules that define what attitudes and behaviors differentiate good group members from bad group members - or acceptable behaviors from unacceptable behaviors. The idea of group norms stems largely from social norms - a similar concept on a much larger societal scale; the concept of social norms stems from sociology.

Political Science:

"The organization of political life, and the ways in which a society is governed, have far-reaching consequences for the nature of the entire society." – Gabriel Almond and Bingham Powell Jr. 5

Political Science is a social science concerned mostly with government systems and political behavior – arguably two of the most powerful forces acting on people and organizations today. Because governments were some of the first large complex organizations to form, much has been learned from these systems. With that said, OB pulls from political science in several ways, but the synthesis of this knowledge is much more subtle than any of the other four fields that are discussed. Ethics, negotiation, and management theories have strong roots in political science. As an example, if we look at management theories and how they’ve evolved over the course of the last two centuries, we can see how politics and ethics shaped organizations through a phase of administrative theory (where managers emerged as a figure who owned the planning, controlling, and organizing processes in the 1920s) to a phase of human relations (where workers were considered more than just the “hands” of the managers), spawning many workplaces changes and laws, including the National Labor Relations, and Social Security Acts.

Economics:

"Incentives are the cornerstone of modern life. And understanding them – or, often, ferreting them out – is the key to solving just about any riddle, from violent crime to sports cheating to online dating." – Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner 6

Economics is referred to as science concerned with the process or system by which goods and services are produced, sold, and bought. In other words, it’s the study of decisions - specifically, how people choose to use the resources they’re given. Like psychology and sociology, economics has significant implications for Organizational Behavior - mostly because it is embedded in just about everything decision-related. The synthesis of economic knowledge, like that of political science, is extremely subtle. Decision-making, for example, which is thought to be a psychological process, has strong roots in economic theory. In economic theory, decisions are thoroughly examined and calculated for the best possible solutions; in OB, tools such as Leadership-Participation Model makes it possible for managers to find the most efficient solution for addressing team-based decisions. This and many other decision-making tools are products of economics.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the multidisciplinary nature of Organizational Behavior has allowed it to draw insights from various fields like anthropology, psychology, sociology, political science, and economics. Each of these disciplines has made significant contributions to our understanding of human behavior in organizational settings. By examining the origins and development of OB, we can better appreciate its practical applications and continue to refine the strategies and techniques used to improve job performance, increase job satisfaction, and enhance the overall success of organizations.

References:

1. Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Wesson, M. J. (2013). Organizational behavior: Improving performance and commitment in the workplace. McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

2. Kluckhohn, C. (1961). Anthropology and the classics. Harvard University Press.

3. Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S. I., Kraiger, K., & Smith-Jentsch, K. A. (2012). The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(2), 74-101.

4. Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd Ed.). New York: Norton.

5. Almond, G. A., & Powell, G. B. (1966). Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

6. Levitt, S. D., & Dubner, S. J. (2009). Freakonomics: a rogue economist explores the hidden side of everything. New York, Harper Perennial.